In Part 1 I provided a high-level overview of different industry sectors that could potentially see the adoption of event cameras. Apart from the challenge of finding the right application, there are several technological challenges before event cameras can reach a mass audience.

Sensor Capabilities

Today’s most recent event cameras are summarised in the table below.

| Camera Supplier | Sensor | Model Name | Year | Resolution | Dynamic Range (dB) | Max Bandwidth (Mev/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iniVation | Gen2 DVS | DAVIS346 | 2017 | 346×260 | ~120 | 12 |

| iniVation | Gen3 DVS | DVXPlorer | 2020 | 640×480 | 90-110 | 165 |

| Prophesee | Sony IMX636 | EVK4 | 2020 | 1280×720 | 120 | 1066 |

| Prophesee | GenX320 | EVK3 | 2023 | 320×320 | 140 | |

| Samsung | Gen4 DVS | DVS-Gen4 | 2020 | 1280×960 | 1200 |

Insightness was sold to Sony, and CelePixel partnered with Omnivision, but hasn’t released a product in the past 5 years. Over the past decade, we have seen pixel arrays grow from 128x128 to 1280x720 (Prophesee’s HD sensor), but higher resolution is actually not always desirable. The last column in the table above describes the maximum number of million events per second that the sensor can handle, which results in GB/s of data for fast moving scenes. In addition, a paper by Gehrig and Scaramuzza suggests that in low-light and high-speed scenarios, performance of high-res cameras is actually worse than when using fewer, but bigger pixels, due to high per-pixel event rates that are noisy and cause ghosting artifacts.

As you can see from the table above, most of today’s event sensors are based on designs from 5 years ago. Different sectors have their own requirements depending on the application, so there are new designs underway. In areas such as defence, higher resolution and contrast sensitivity, as well as capturing the short/mid range infrared spectrum, is vital because range is so important. SCD USA made the MIRA 02Y-E available last year that includes an optional event-based readout, to enable tactical forces to detect laser sources. Using the event-based output, it advertises a frame rate of up to 1.2 kHz. In space, the distances to the captured objects are enormous, and therefore high resolution and light sensitivity are of utmost importance. As mentioned in Part 1, there are now companies focusing on building event sensors for aerospace and defence, given the growing allocation of resources in that sector.

In short-range applications such as eye tracking for wearables, a sensor at lower resolution but high dynamic range and ultra-low power modes is going to be more relevant. Prophesee’s GenX320 is designed for that.

For scientific applications, NovoViz recently announced a new SPAD (single photon avalanche diode) camera using event-based outputs, where outputting full frames would be way too costly.

Over the next few years we’ll see new designs emerging, although I would argue that two decades of research using the binary event output format has mostly resulted in converting events to some form of image representation, in order to apply the tools and frameworks that are already mature. I think that’s why we’re seeing new hybrid vision sensors emerging, which try to rethink the event output format. At ISSCC 2023, two of three papers presenting new event sensors showed the introduction of asynchronous event frames.

| Sensor | Event output type | Timing & synchronization | Polarity info | Typical max rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sony 2.97 μm | Binary event frames (two separate ON/OFF maps) | Synchronous, ~580 µs “event frame” period | 2 bits per pixel (positive & negative) | ~1.4 GEvents/s |

| Sony 1.22 μm, 35.6 MP | Binary event frames with row-skipping & compression | Variable frame sync, up to 10 kfps per RGB frame | 2 bits per pixel (positive & negative) | Up to 4.56 GEvents/s |

| OmniVision 3-wafer | Per-event address-event packets (x, y, t, polarity) | Asynchronous, microsecond-level timestamps | Single-bit polarity per event | Up to 4.6 GEvents/s |

The Sony 2.97 μm chip uses aggressive circuit sharing so that four pixels share one comparator and analog front-end. Events are not streamed individually but are batched into binary event frames at fixed frequency every ~580 µs, with separate maps for ON and OFF polarity. This design keeps per-event energy extremely low (~57 pJ) and allows the sensor to reach ~1.4 GEvents/s without arbitration delays. The event output is already frame-like, and thus fits naturally into existing machine learning pipelines that expect regular image-like input at deterministic timing.

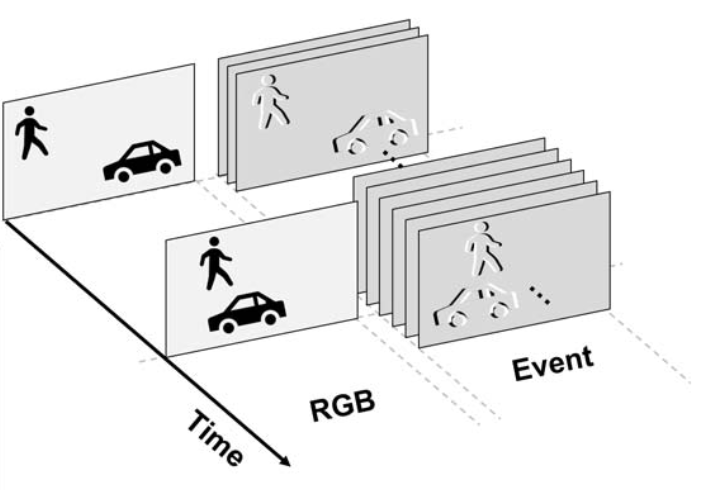

The Sony 1.22 μm hybrid sensor aimed at mobile devices combines a huge 35.6 MP RGB array with a 2 MP event array. Four 1.22 µm photodiodes form each event pixel (4.88 µm pitch). The event side operates in variable-rate event-frame mode, outputting up to 10 kfps inside each RGB frame period (see picture from the paper below). On-chip event-drop filters and compression dynamically reduce data volume while preserving critical motion information for downstream neural networks (e.g. deblurring or video frame interpolation). To me the asynchronous data capture of event frames that encode change seems like a practical way forward. I think that frame rates up to 100 Hz are sufficient for most applications.

Kodama et al. presented a Sony 1.22 μm hybrid sensor that outputs variable-rate binary event frames next to RGB.

Kodama et al. presented a Sony 1.22 μm hybrid sensor that outputs variable-rate binary event frames next to RGB.

The OmniVision 3-wafer is closer to the classic DVS concept but shows what’s possible: A dedicated 1MP event wafer with in-pixel time-to-digital converters stamps each event with microsecond accuracy. Skip-logic and four parallel readout channels give an impressive 4.6 GEvents/s throughput. It’s good for ultra-fast motion analysis or scientific experiments where every microsecond matters. Picture from the paper comparing RGB and event output below.

Guo et al. presented a new generation of hybrid vision sensor that outputs binary events.

Guo et al. presented a new generation of hybrid vision sensor that outputs binary events.

I think that today’s binary microsecond spikes are rarely the right format for most applications. Much like Intel’s Loihi 2 shifted from binary spikes to richer spike payloads because they realised that the communication overhead was too high otherwise, future event cameras are becoming more practical by exploring frame-like representations. They could also emit something in between binary events and frames, such as multi-bit “micro-frames” or tokenizable spike packets. These would represent short-term local activity and could be directly ingested by ML models, reducing the need for preprocessing altogether.

Ideally there’s a trade-off between information density and temporal resolution that can be chosen depending on the application. In either case, the event camera sensor has not reached its final form yet. People are still experimenting with how events should be represented in order to be compatible with modern machine learning methods.

Event Representations

Most common approaches aggregate events into image-like representations such as 2d histograms, voxel grids, or time surfaces. These can then be used to fine-tune deep learning models that were pre-trained on RGB images. This leverages the breadth of existing tooling built for images and is compatible with GPU-accelerated training and inference. Moreover, it allows for adaptive frame rates, aggregating only when there’s activity and potentially saving on compute in case there’s little activity in the scene. But this method discards much of the fine temporal structure that event cameras provide today, and it’s also not as efficient as it could be: the tensors produced are full of zeros, and in order to get sufficient signal, you have to accumulate for hundreds of milliseconds if you’re capturing a slow activity. This becomes problematic for real-time applications where a long temporal context is needed but high responsiveness is crucial.

We still lack a representation for event streams that works well with modern ML architectures while preserving their sparsity. Event streams are a new data modality, just like images, audio, or text, but one for which we haven’t yet cracked the “tokenization problem.” At first sight, an event stream, one event after the other, is a perfect match for today’s capable sequence models. But a single binary event contains very little semantic information. Unlike a word in a sentence, which can encode a complex concept, even a dozen binary events reveal almost nothing about the scene. This makes direct tokenization of events inefficient. What we need is a representation that can summarize local spatiotemporal structure into meaningful, higher-level primitives, to represent event streams as a sequence of tokens that is directly dependent on activity in the scene. Less movement in the scene would result in fewer tokens being emitted, which saves compute.

Models

At their core, event cameras are change detectors, which means that we need memory in our machine learning models to remember where things were before they stopped moving. We can bake memory into the model architecture by using recurrence or attention. For example, Recurrent Vision Transformers and their variants maintain internal state across time and can handle temporally sparse inputs more naturally. These methods preserve temporal continuity, but there’s a catch: most of these methods still rely on dense, voxelized inputs. Even with more efficient state-space models replacing LSTMs and BPTT (Backpropagation Through Time) with much faster training strategies, we’re still processing a lot of zeros. Training is faster, but inference is still bottlenecked by inefficient representations. There are however some newer types of models that try to exploit the sparsity in event data, both temporally (inputs arrive irregularly) and spatially (any input has fewer zeros).

Graph Neural Networks

Graphs, especially dynamic, sparse graphs, are an interesting abstraction to explore. Each node could represent a small region of correlated activity in space and time, with edges encoding temporal or spatial relationships. Recent work such as DAGr, ACGR, eGSMV, or HUGNet v2 show that GNNs provide a natural fit for event data.

Despite their differences, these papers converge on a common recipe: combine fast, event-level graph updates (for responsiveness at microsecond scales) with slower contextual aggregation (for stability and accuracy). DAGr fills blind time between low-rate frames using an asynchronous GNN; ACGR unifies frame and event nodes in a single sparse graph at ~200 Hz; eGSMV explicitly splits spatial vs. motion graphs; and HUGNet v2 mixes an event branch with a periodic aggregation branch, cutting prediction latency by three orders of magnitude while preserving accuracy. They avoid pure event-by-event updates because they are too noisy and costly, but batching everything into frames also defeats the purpose. GNNs strike a balance by structuring sparse events into dynamic graphs and then layering in context only where needed.

This hybrid design makes GNNs a strong candidate for the “tokenization” problem of event vision: they compress raw events into graph-structured tokens that carry more meaning than individual ON/OFF spikes, while remaining activity-driven and sparse. Still, these methods struggle with scalability because graph construction is memory- and bandwidth-heavy, and irregular node–edge layouts map poorly to today’s GPUs. Specialized accelerators for graph processing may ultimately be required if these representations are to run in real-world embedded systems. By combining event cameras with efficient “graph processors,” we could offload the task of building sparse graphs directly on-chip, producing representations that are ready for downstream learning. Temporally sparse, graph-based outputs could serve as a robust bridge between raw events and modern ML architectures.

State-space Models

Following the success of VMamba for RGB inputs, state-space models (SSMs) approach perception as a continuous-time dynamical system with a compact hidden state that can be discretized at any step size. This flexibility is particularly valuable for event cameras, because it allows a user to train at one input rate and deploy at another simply by changing the integration step, without needing to retrain. SSMs scale linearly in sequence length so you can extend (fine-grained) temporal context without exploding compute. They also maintain a cheap, always-on scene state that updates with each micro-batch of activity, which is particularly advantageous on embedded systems to save memory.

Zubić and colleagues show that combining S4/S5-style SSM layers with a lightweight Vision Transformer backbone leads to faster training that is about a third quicker than RNN-based recurrent transformers, and much smaller accuracy loss when the input frequency at deployment is higher than during training.

Yang et al. introduced SMamba, which builds on the Mamba/SSM idea and adds adaptive sparsification. By estimating spatio-temporal continuity, it discards blank or noisy tokens, prioritizes scans so informative regions interact earlier, and mixes channels through a global channel interaction step. On datasets such as Gen1, 1Mpx, and eTram, this approach reduces FLOPs by roughly 22–31 % relative to its dense baseline.

For optical flow, a spatio-temporal SSM encoder can estimate dense flow from a single event volume, bypassing RAFT-style iterative refinement. This method achieves about 4.5 times faster inference and roughly eight times fewer MACs than a recent iterative method (TMA) while maintaining competitive endpoint error, illustrating that SSMs can replace costly recurrence while preserving temporal precision.

PRE-Mamba’s approach is interesting because it turns the event camera’s weakness of generating large amounts of data for dynamic scenes into a benefit. The authors use a multi-scale SSM inside a point-based pipeline over a 4D event cloud for weather-robust event deraining. The key architecture lesson is that minimal spatio-temporal clustering combined with an SSM can carry long temporal context efficiently and with a small parameter footprint.

Several practical guidelines emerge for building with SSMs. They make it feasible to train once and deploy anywhere along the time axis: if a system must run at 10 Hz in the lab and 100 Hz on-device, it is enough to rescale the discretization step without any fine-tuning. In terms of architecture, the most stable pattern across papers is to use an SSM for temporal aggregation paired with a lightweight spatial mixer, such as local attention or a convolution, which preserves long memory without incurring transformer-scale spatial costs. Efficiency can be improved by exploiting sparsity without sacrificing global context: instead of relying on purely local or windowed attention, prune tokens based on spatio-temporal continuity, discard obvious background or noise, and still scan globally over what remains, following the SMamba strategy. For deployment, diagonal or parallel-scan variants such as S4D, S5, or Mamba-style selective scans are recommended because they run naturally in streaming mode.

For event vision, SSMs provide an effective “scene memory” primitive because they can handle long sequences more efficiently than transformers and support variable timing. The emerging recipe that scales well is to use small adaptive windows of voxel grids, micro-frames, or serialized patches, add light spatial mixing, apply an SSM for temporal modeling, and optionally incorporate sparsification to skip inactive regions. This keeps latency low when activity is sparse and allows increasing batch size during heavy traffic without rewriting the model or retraining for different rates.

Spiking neural networks

Biological neurons are extremely complex, and there’s a whole world to be modeled in each cell. The Chan-Zuckerberg initiative on virtual cells, and also DeepMind’s cell simulations go to great lengths in an effort to model it. Because cells are so complex, projects like the Human Brain Project (HBP) tried to simulate brain activity by using higher-level abstractions on a larger scale. HBP helped pave the way for spiking neural networks (SNNs), which are sometimes touted as a natural fit for event data. But in their traditional form, with binary activations and reset mechanisms, researchers get too attached to handcrafted abstractions, such as leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) models, which have shown inferior performance compared to other architectures. I’m reminded of an Open Neuromorphic talk by Timoleon Moraitis last year, where he talks about drawing inspiration from biological principles, without dogmatically copying them.

Deep learning started out with 32-bit floating point, dense representations, and neuromorphic started out on the other end of the spectrum at binary, extremely sparse representations. They are converging, with neuromorphic realising that binary events are expensive to transmit and process, and deep learning embracing 4-bit activations and 2:4 structured weight sparsity. A recent paper even proposes binary neural networks, which shows that the research community is surprisingly resistant to the learnings of the past. So let’s not get hung up on the artificial neuron model itself, and instead use what works well, because the field of machine learning is moving incredibly fast.

One more note on scale. SNNs in their classic form are plagued with all the difficulties of training RNNs, which means that it’s super slow to train and therefore unfeasible to scale up. When I initiated the SNN library benchmarks to find out which library can train the fastest, people told me that neuromorphic is all about the need to find novel algorithms, and not about training fast. But that’s simply not true. Scale is important, and for scale you need fast training. There’s a strong bias in the neuromorphic community to focus on tiny models and efficiency. But nowadays, in order to get an efficient edge model that generalises well, you first want a larger AI model that you can optimise, using pruning, distillation, or quantisation. Or you use it as a teacher, and make the tiny model a student of a larger model. Even a 50-fold reduction in power consumption won’t convince any client if the model cannot cope with some distribution shifts in the input.

Processors

Running models efficiently on event data is as much a hardware problem as a modelling one. GPUs remain the default accelerator, but they are poorly matched to the irregular memory access patterns of event streams. Even if the inputs are sparse, most compute in intermediate layers ends up dense, so energy savings from “skipping zeros” specifically for event inputs are negligible.

State-space models have recently been shown to run well on neuromorphic substrates: for example, Meyer et al. mapped an S4D variant to Intel’s Loihi 2, exploiting diagonalized state updates to reduce inter-core traffic and outperforming a Jetson GPU in true online inference. This demonstrates that compact, recurrent stateful models can benefit from specialized hardware when communication costs dominate. Intel’s Loihi was the most advanced neuromorphic chip, and since large-scale modelling of the brain and constrained optimizations they’ve come a long way to exploit the asynchronous hardware in a more practical way. I would love to see an efficient edge chip coming out of this, although that’s not really Intel’s game I’m afraid.

For GNN-based event processing, new dedicated accelerators are emerging. The EvGNN hardware prototype (IEEE 2024) shows that integrating graph construction and message passing directly on-chip can reduce latency by an order of magnitude and improve energy efficiency by over 10× compared to GPUs. Crucially, it processes events asynchronously, triggering computation only when new data arrives, which aligns naturally with the event-camera principle. This kind of co-design, sensor output coupled tightly with graph-oriented hardware, may be necessary if graph representations are to be deployed beyond research demos.

Some argue that because event cameras output extremely sparse data, we can save energy by skipping zeros in the input or in intermediate activations. But while the input might be much sparser than an RGB frame, the bulk of the computation happens in intermediate layers and works with higher-level representations, which are similar for both RGB and event inputs. Thus in AI accelerators we can’t exploit spatial event camera sparsity, and inference cost between RGB and event frames are essentially the same for reasonably sized models. We might get different input frame rates / temporal sparsity, but those can be exploited on GPUs as well.

On mixed-signal hardware, rules are different, but maintaining state is always expensive. You pay in power (multiplexing) or chip size (analog). A basic rule for analog to my understanding is: if you need to convert from analog to digital too often, for error correction or because you’re storing states, your efficiency gains go out of the window. Mythic AI had to painfully learn that and almost tanked, and also Rain AI pivoted from its original analog hardware and faces an uncertain future. There’s a major algorithmic challenge to this as well, because the analog components are noisy, but the potential rewards for doing it efficiently are high. There’s some interesting work about 3d analog in-memory computing coming out of IBM!

The asynchronous compute principle is key for event cameras, but naïve asynchrony is not constructive. Think about cars entering a roundabout, and the flow of traffic without any traffic lights. When the traffic volume is low, every car is more or less in constant motion, and latency to cross the roundabout is minimal. As the volume of traffic grows, a roundabout becomes inefficient, because the movement of any car depends on the decisions of cars nearby. For high traffic flow, it becomes more efficient to use traffic lights to batch process the traffic for multiple lanes at once, which achieves the highest throughput of cars.

The same principle applies for events. When you have few pixels activated, you achieve the lowest latency when you process them as they come in one by one, like cars in a roundabout. But as the amount of events / s increases, you will want to process the events in batches, like with traffic lights. Ideally the size of the batch depends on the event rate.

Making a custom chip for a single architecture, whether LSTMs, SNNs, or a bespoke event-processing pipeline, is a huge bet. History isn’t kind to these bets. The past decade saw multiple companies attempt specialised RNN accelerators and most collapsed, pivoted, or were absorbed once general-purpose GPUs and NPUs caught up. Unless a camera produces representations that map cleanly onto widely available hardware, the software ecosystem will outrun the silicon.

For more info about neuromorphic chips, I refer you to Open Neuromorphic’s Hardware Guide.

Conclusion

Event cameras won’t reach mainstream adoption until they break away from the legacy of microsecond-precision binary spikes and embrace output formats that carry richer, more structured information. The core challenge is representation: modern ML systems are built around structured tokens such as patches, words, or embeddings, not floods of binary impulses.

A workable solution will likely follow a two-stage architecture: a lightweight, streaming tokenizer that aggregates local spatiotemporal activity into short-lived micro-features, followed by a stateful temporal model that reasons over these features efficiently. Such representations preserve sparsity, maintain temporal fidelity, and scale naturally under variable scene activity.

If I had to bet on a commercial trajectory today, it would be hybrid sensors that pair variable-rate event frames with standard RGB output, producing a sparse token stream processed by compact state-space models on embedded GPUs or specialized edge accelerators. Sacrificing some raw temporal resolution in exchange for more semantically meaningful, compressible aggregates is a practical and likely necessary trade-off. The goal is not to create pretty images but to produce machine-readable signals that map cleanly onto existing AI hardware.

The scalable recipe looks something like this: generate tokens that carry meaning, train them with a mix of cross-modal supervision and self-supervision that reflects real sensor noise, maintain a compact and cheap-to-update scene memory, and make computation conditional on activity rather than a fixed clock. Key research directions include dynamic graph representations for efficient tokenization, state-space models for low-latency inference at the edge, and lossy compression techniques that can shrink event streams without destroying semantic content.

Finally, application needs should guide sensor and model design. Gesture recognition doesn’t require microsecond timing. Eye tracking doesn’t need megapixel resolution. And sometimes a motion sensor-triggered RGB camera is the most pragmatic solution. Event cameras don’t need to replace conventional vision, they just need to become usable enough, in the right form, to complement it.