We use them every day and take them for granted: cameras in all their endless shapes and forms. The field of modern computer vision, the ability of machines to see, is based on the common output format of those sensors: frames. However, the way we humans perceive the world with our eyes is very different. Most importantly, we do it with a fraction of the energy needed by a conventional camera. The field of neuromorphic vision tries to understand how our visual system processes information, in order to give modern cameras that same efficiency and it looks like a substantial shift in technology. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Conventional imaging technology

We are so focused on working with data that modern cameras provide, that little thought is given about how to capture a scene more efficiently in the first place. Current cameras acquire frames by reading the brightness value of all pixels at the same time at a fixed time interval, the frame rate, regardless of whether the recorded information has actually changed. A single frame acts as a photo; as soon as we stack multiple of them per second it becomes a motion picture. So far so good. This synchronous mechanism makes acquisition and processing predictable. But it comes with a price, namely the recording of redundant data. And not too little of it!

Image blur can occur in a frame depending on the exposure time.

Image blur can occur in a frame depending on the exposure time.

Our visual system

The human retina has developed to encode information extremely efficiently. Narrowing down the stimuli of about 125 million photoreceptors, which are sensitive to light to just 1 million ganglion cells which relay information to the brain, the retina compresses a visual scene into its most essential parts.

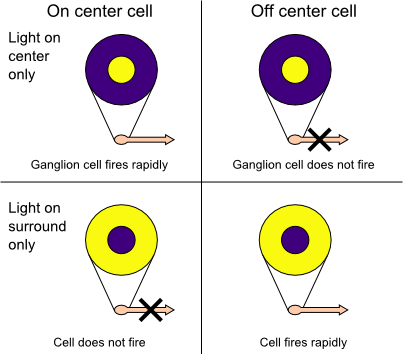

Center surround receptive fields in the mammalian retina, source

Center surround receptive fields in the mammalian retina, source

Photoreceptors are bundled into receptive fields of different sizes for each retinal ganglion cell. The way a receptive field is organised into center and surround cells allows ganglion cells to transmit information not merely about whether photoreceptor cells are exposed to light, but also about the differences in firing rates of cells in the center and surround. This allows them to transmit information about spatial contrast. They are furthermore capable of firing independently of other ganglion cells, thus decoupling the activity of receptive fields from each other. Even if not triggered, a retinal ganglion cell will have a spontaneous firing rate, resulting in millions of spikes per second that travel along the optic nerve. It is thought that in order to prevent the retinal image from fading and thus be able to see the non-moving objects, our eyes perform unintentional rapid ballistic jumps called micro-saccades. This movement only happens once or twice per second, so in between micro-saccades, our vision system probably relies on motion. To put it in a nutshell, our retina acts as a pre-processor for our visual system, extracting contrast as the most important information that then travels along the optical nerve to the visual cortex. In the cortex it is processed for higher-level image synthesis such as depth and motion perception.

Taking inspiration from nature

Towards the end of the 80s, a scientist at Caltech named Carver Mead spawned the field of Neuromorphic Engineering, when one of his students called Misha Mahowald developed a new stereo vision system. Taking inspiration from the human visual system, she built what would become the first silicon retina in the early 90s. It was based on the same principle of center surround receptive fields in the human retina, that emit spikes independently of each other depending on the contrast pattern observed.

Misha Mahowald (circa 1992) in the ‘Carverland’ lab at Caltech, testing her stereocorrespondence chip. Photo credit: Rodney Douglas.

Misha Mahowald (circa 1992) in the ‘Carverland’ lab at Caltech, testing her stereocorrespondence chip. Photo credit: Rodney Douglas.

Although Misha drafted the beginning of a new imaging sensor, it did not provide a practical implementation at first. In response, the neuromorphic community simplified the problem by dropping the principle of center-surround pixels. Instead of encoding spatial contrast across multiple pixels which needed sophisticated circuits, the problem could be alleviated by realising a circuit that could encode temporal contrast for single pixels. That way, pixels could still operate individually as processing units just as receptive fields in the retina do and report any deviations in illuminance over time. It would take until 2001 when Tetsuya Yagi at Osaka University and Tobi Delbrück at UZH/ETH in 2008 publish about the first refined temporal contrast sensors, the event cameras as they are known today.

Paradigm Shift

Standard cameras capture absolute illuminance at the same time for all pixels driven by a clock and encoded as frames. One fundamental approach to dealing with temporal redundancy in classical videos is frame difference encoding. This simplest form of video compression includes transmitting only pixel values that exceed a defined intensity change threshold from frame to frame after an initial key-frame. Frame differencing is naturally performed in post-processing, when the data has already been recorded.

Trying to take inspiration from the way our eyes encode information, neuro-morphic cameras capture changes in illuminance over time for individual pixels corresponding to one retinal ganglion cell and its receptive field.

![]() Principle of how ON and OFF events are generated for each pixel.

Principle of how ON and OFF events are generated for each pixel.

If light increases or decreases by a certain percentage, one pixel will trigger what’s called an event, which is the technical equivalent of a cell’s action potential. One event will have a timestamp, x/y coordinates and a polarity depending on the sign of the change. Pixels can fire completely independently of each other, resulting in an overall firing rate that is directly driven by the activity of the scene. It also means that if nothing moves in front of a static camera, no new information is available hence no pixels fire apart from some noise. The absence of accurate measurements of absolute lighting information is a direct result of recording change information. This information can be refreshed by moving the camera itself, much like a microsaccade.

So how do we now get an image from this camera? The short answer is: we don’t. Although we can of course add together all the events per pixel to get an idea of how much the brightness changed (‘binning’), in reality this will not be a reliable estimate, as the electronics of the camera will cause a bit of background noise. As such, the error of your estimate only grows over time.

An event-camera will only record change in brightness and encode it as events in x, y and time. Colour is artificial in this visualisation. Note the fine-grained resolution on the t-axis in comparison with the frame animation earlier.

An event-camera will only record change in brightness and encode it as events in x, y and time. Colour is artificial in this visualisation. Note the fine-grained resolution on the t-axis in comparison with the frame animation earlier.

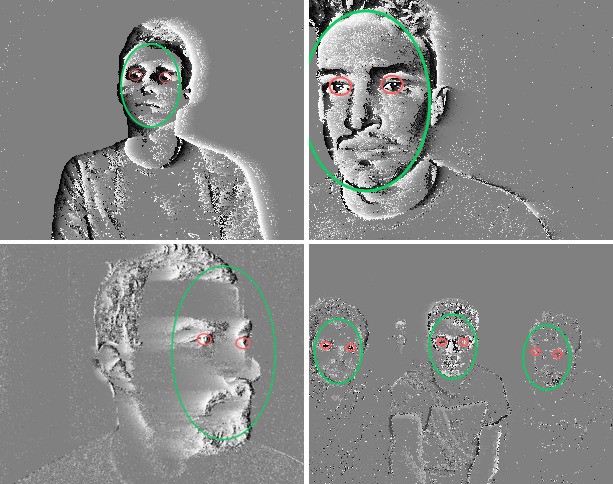

Overall an event-camera has three major advantages: Since pixel exposure times are decoupled of each other, very bright and very dark parts can be captured at the same time, resulting in a dynamic range of up to 125dB. In autonomous vehicles, where the lighting can change very quickly or exposure of a single bright spot such as the sun or a reflection should not interfere with the rest, this can save lives. The decoupled, asynchronous nature furthermore frees bandwidth so that changes for one pixel can be recorded at a temporal resolution and latency of microseconds. This makes it possible to track objects with very high speed and without blur. The third advantange is low power consumption due to the sparse output of events, which makes the camera suitable for mobile and embedded applications. Remember that when nothing in front of the camera moves, no redundant data is recorded by the sensor which reduces computational load overall. It also relieves the need for huge raw data files. Current drawbacks for most commercially event-cameras available today are actually further downstream, namely the lack of hardware and algorithms that properly exploit the sparse nature of an event-camera’s data. Rethinking even the most basic computer vision algorithms without frames takes a considerable effort. I published some work about purely event-based face detection, have a look at the video!

Some snapshots of my work on face detection with event cameras that relies on eye blinks.

Some snapshots of my work on face detection with event cameras that relies on eye blinks.

Be on the lookout

So why are these sensors becoming interesting just now? Humanity has learnt to build powerful synchronous hardware such as GPUs that enable high performance, high throughput computing. They provide the power necessary to work with dense image information that are frames. But we’re only ever veering away from the efficiency of a biological system in terms of information processing. Understanding the biological principles of a complex system such as human vision will therefore help create artificial sensors that resemble their biological equivalents. This bears the potential of a low-power sensor with fine-grained temporal resolution.

Since their original inception a few decades ago, it has been quite a journey. Labs at Zurich, Sydney, Genua, my lab in Paris, Pittsburgh, Singapore and many more are exploring the concept of event-based computation. Start-up companies such as Prophesee or Celex compete with established players such as Samsung and Sony in the race to find promising applications for this interesting imaging technology. Potential industry candidates include the automotive industry, neural interfaces, space applications, autonomous agents, … you name it!

If you want to know more about algorithms for event-based cameras, I recommend this survey paper for you. Stay tuned for more articles about neuromorphic engineering on this space! You can also reach out to me via Twitter or check out some code on Github.

Last but not least I want to thank my former colleague Alexandre Marcireau who made the event visualisations for this article possible with rainmaker!

My friend Omar causes the camera to heat up.

My friend Omar causes the camera to heat up.